27 02

18 04

2026

Light Approximation

Vácav Boštík, Hugo Demartini, Milan Grygar, Daniel Hanzlík, Stanislav Kolíbal, Radoslav Kratina, František Kupka, Karel Malich, Jiří Matějů, Jan Poupě, Zdeněk Sýkora, Zdeněk Trs

Curated by Jan Dotřel

God created nights full of dreams and mirrors

so that man might know he is a reflection and a vanity.

That is why they frighten us.

Jorge Luis Borges

The search for essence, transcendence and reduction can form the basis of artistic expression and be understood as geometric abstraction. This way of thinking has deep roots in Czech art history, and the exhibition 'Approximation of Light' focuses on this specific area of thought.

The term 'approximation' has several meanings. In mathematics, it represents replacing complex systems with simpler ones; in a general sense, however, it expresses an ongoing process of approximation. A similar pattern can be seen in art with abstract tendencies, which is based on the gradual removal of form and the search for the essence of the visual code in its simplest form.

This exhibition aims to showcase a select group of Czech artists from past decades and emphasise the significance and evolution of this artistic style among contemporary artists.

The origins of reduced painting can be found in a global context, particularly in the work of Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian. Within the realm of geometric painting, certain tendencies towards austerity and reductionism can be observed in the works of Jindřich Štýrský and Toyen. However, the real milestone was František Kupka, who paved the way for a whole new generation of artists working in this style. His transformation from Cubism-Orphism, characterised by the use of bright colours, established him as one of the founders of abstract art worldwide.

Zen Buddhism is a culture closely associated with reduction, spiritual transcendence and the removal of matter. Minimalist temples, which emphasise the meaning of empty space and encourage meditative contemplation, are spaces of abstraction par excellence. The architecture of the exhibition, which evokes the joints of floor beams inside a Zen temple, alludes to this concept. Viewers can follow a trajectory that guides them to individual works. However, if they decide to explore independently, they can deviate from this path at any time.The predominance of truth as correct judgment in the modern age compels us to approach art indirectly and in a mediated way; art is no longer the very air breathed by our souls, as it was for Greek science, which sees ideas and whose proofs are pieces of architecture.

For us, abstraction is the natural disposition of the spirit, and this is certainly evident in the art of our time.

Jan Patočka

The position of the subject in space is the decisive determinant of our consciousness. The landscape, the horizon or the cosmos can be considered as spiritual boundaries within which we move, and the limits of which we have been trying to expand for thousands of years.

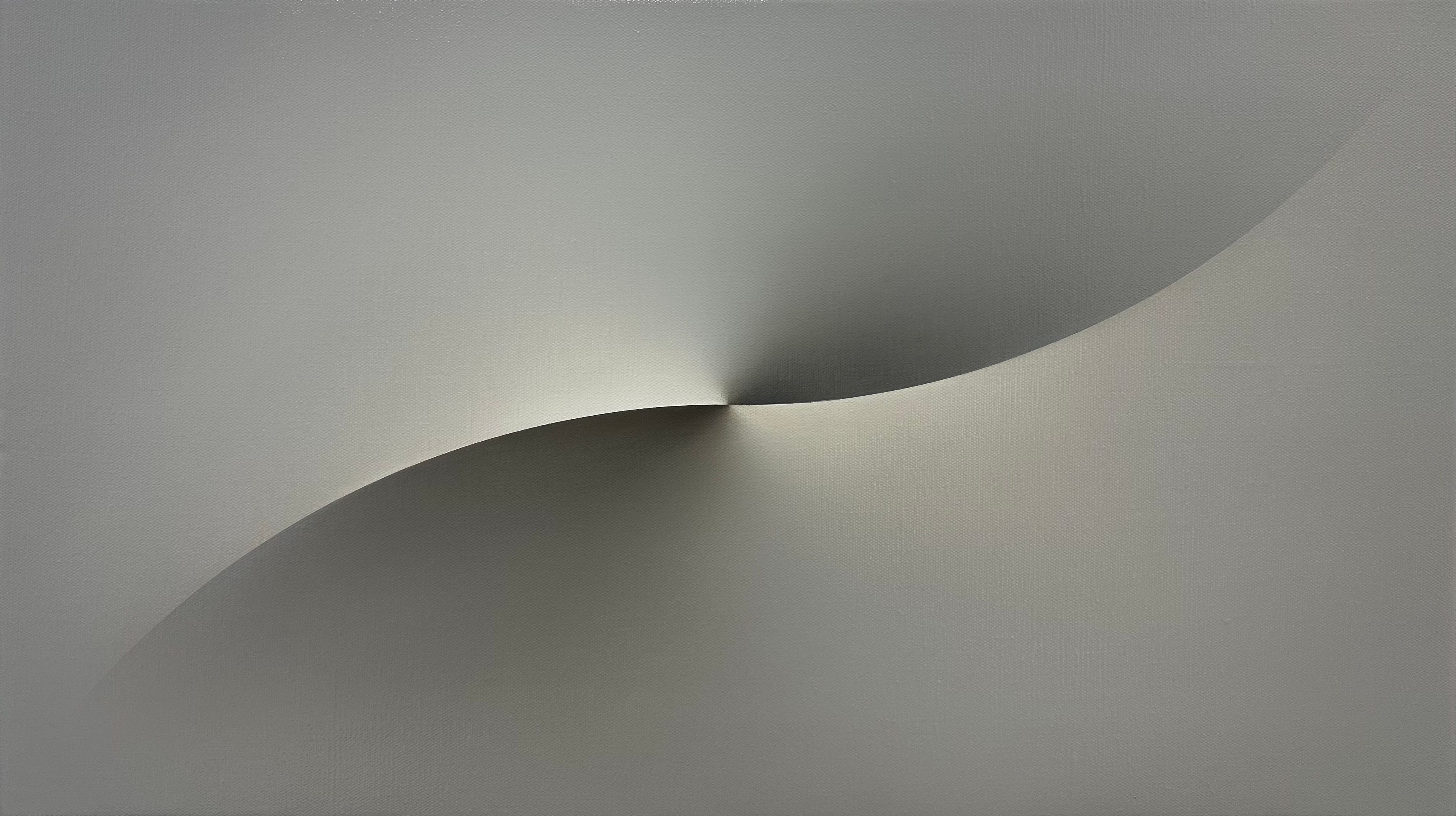

The topology of the landscape was already important to Karel Malich during his mimetic period. Over time, he began to simplify its representation, moving from minimalist spaces to supremely abstract gestures flowing across a white surface. In this case, gesture is a very important concept, as it occurs at an automated and archetypal level, which is rather rare in geometric abstraction.

In contrast, another interpreter of the natural world is Zdeněk Trs, for whom the earthly landscape is insufficient and who often moves to the universal plane. This artist is Zdeněk Trs. Earthly physical phenomena and the laws of celestial mechanics have their own specific reasons and codes for arising. These properties are often inscribed in mathematical dependencies and geometric premises. When we observe phenomena such as lightning, whirlwinds, lunar halos or solar eclipses, their formal origins are hidden beneath layers of geometry, much like the quiet paintings of Zdeněk Trs.

The natural world around us reveals itself only when we are inclined to pay attention and contemplate in peace. There is no light without darkness, and vice versa. Every light casts a shadow, and every shadow can be illuminated. Perhaps we find ourselves between these two entities.

In his excellent essay, 'Rationality of Poetry or Poetry of Rationality', Jan Sekera draws a comparison between Stanislav Kolíbal's work and Platonic geometry. The concept of Plato's cave represents an unattainable ideal that radiates divine values with its inner light. Similarly, Hugo Demartini devoted his entire professional career to a quest for perfection in the most complex aspect of our reality: the sphere.

The significance of the natural world and its reflection in art is a key theme. Milan Grygar took an avant-garde approach to observing reality, combining acoustics and visual form in his work. In their imaginary journey to the core, all of these artists delved very deep. The deeper they went, the more their works resembled a tabula rasa.

All artists, whether primitive or sophisticated, have remained concerned with the problem of chaos.

Barnett Newman

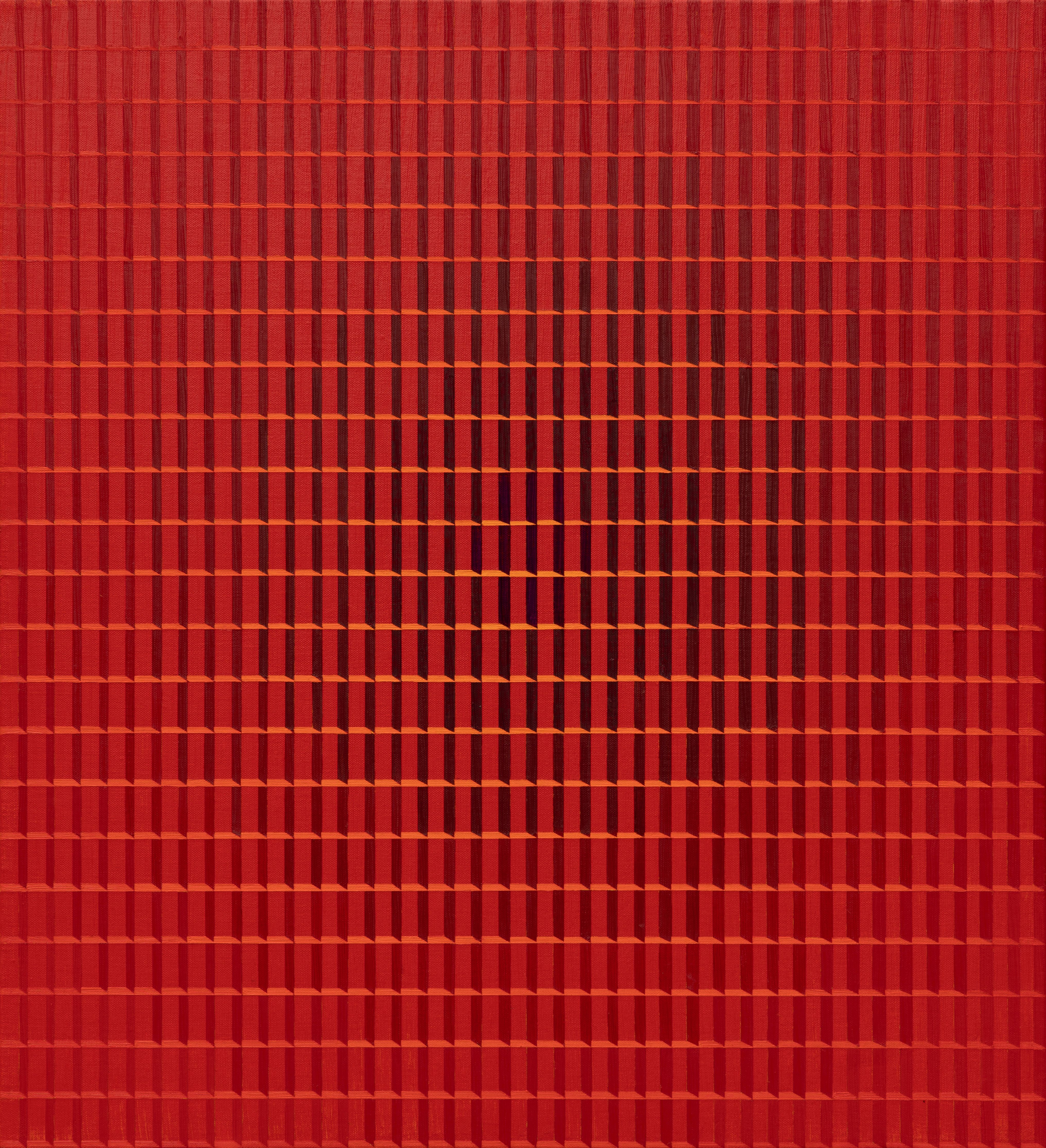

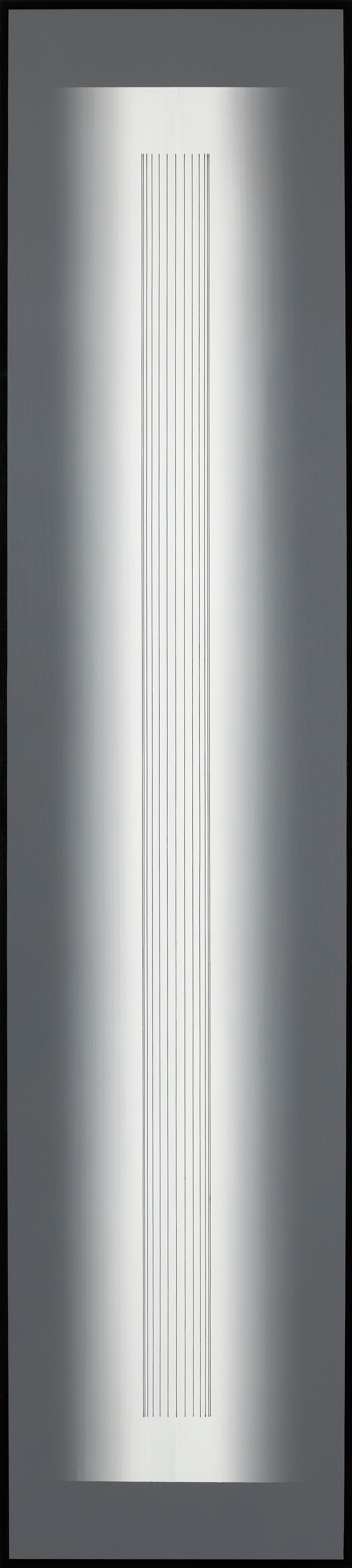

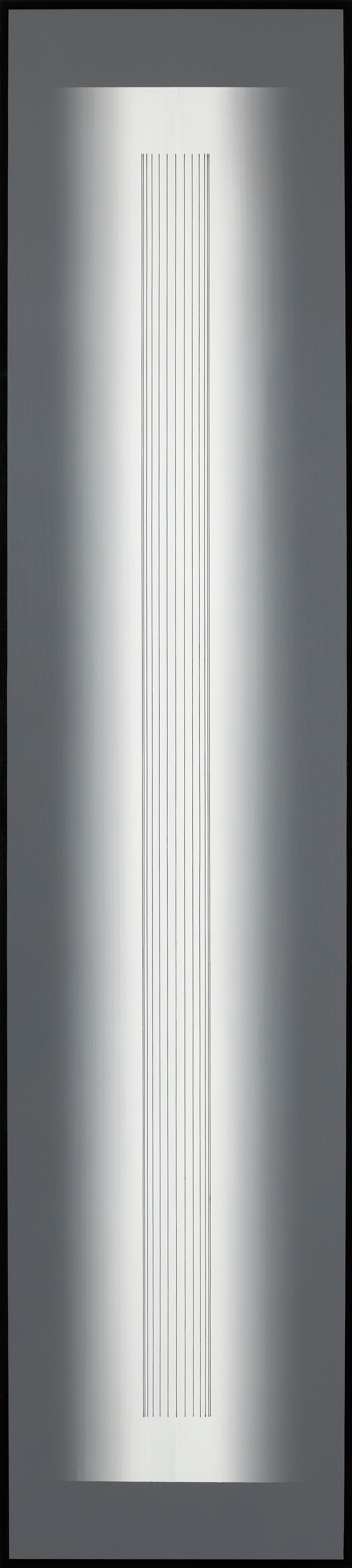

The stories of the following artists are constructed around the idea of building matter, form and space. Standing before Daniel Hanzlík's paintings, we witness the complex layering of acrylic pigments, which ultimately present us with metaphorical gates of knowledge. Light has wave-like and particle-like properties, and in Hanzlík's work, it often manifests itself through transitions and gradients. Thanks to its simplicity and contrast, light can undermine the veil of knowledge much more easily.

At the Bauhaus school in Weimar, Paul Klee defined the key concept of structure, which inspired Zdeněk Sýkora. He systematically generated new dynamic compositions from repeating shapes, creating higher-order superstructures. These are not examples of Op Art, but rather of Euclidean planimetry, which provides a deeper description of our reality.

Radoslav Kratina was undoubtedly the most revolutionary sculptor of this Czech group. Like the Surrealists, he was interested in creating art that was free from content and did not aim to record secondary associations. He created works that existed purely as works of art. This is a bold and challenging approach that touches on the essence of abstraction.

Jan Poupě's fictional world is a complex labyrinth offering a new level of immersion at every turn. His utopian discourse unravels the threads of certain fields where the laws of physics sometimes apply and sometimes do not, setting our imagination in motion. The latest series of paintings created for this exhibition focuses more on the laws of colour placement and transition, which contrast with each other in a complementary way. Contrast is something to which the human eye is naturally sensitive. It helps us to distinguish one entity from another, ensuring legibility and understanding. This strategy makes this cycle one of the most abstract that Jan Poupě has ever undertaken.

The transformation of profane existence into another, absolute state — moksha, nirvana, or asamskrita — which it is tempting to regard as a parallel to the Suprematist state of non-objectivity.

Kazimir Malevich

The existential quest for knowledge of space, matter and time has been the eternal nemesis of humankind. Many cultures emphasise the importance of light and emptiness. For some artists, the question of supreme abstraction and the search for emptiness is a lifelong mission.

In the Czech context, we can observe the convergence of two pilgrims in search of these sacred places: Václav Boštík and Jiří Matějů. Matějů's paintings cannot be perceived materially or iconographically. Taking this approach would lead to misinterpretation.

A more appropriate way to understand them is to experience them first-hand. The viewer does not merely look at a two-dimensional image; the image itself observes the viewer.

A Zen monk looking at a fallen leaf can see the entire tree, including its roots, in a single visual experience. We can observe a similar discipline of visual cognition in the work of Václav Boštík, who based his work on deep spirituality. The intersection of the spiritual and material worlds, formed by fields, vibrations and symmetries, is the basis of his perception.

Try to imagine the quantum world, singularity or emptiness. This is very difficult to do. Similarly, it is difficult to make visible that which cannot be depicted. This is the sacred goal of true art.